Working with State Machines in Angular

-

Stefanos Lignos

Stefanos Lignos - Modified Fr Aug, 2025

Stop trying to make a complex system reliable by testing it, test yourself by trying to rely on simplicity.

I thought that it would be nice to start with my personal motto on software development and of course, part of this article revolves around this notion. However, you may wonder how the complexity of software is related to State Machines. Keep reading and I hope I will answer this question in the following paragraphs.

We’re going to use a library called XState to build the state machines in an Angular app. However, keep in mind that the goal of this article is not to be a detailed guide for implementing an Angular app using this library. It’s the first approach to investigate how XState could be used in an Angular application. Also an attempt to explain why/how statecharts can reduce the complexity of our codebase and development process.

Complexity

First, let’s define what we mean when we refer to the term complexity. We say that a system is complex when we struggle to understand and explain it. And this lack of understanding is the root cause of the main problems that come with the complexity. This includes unreliability, missed deadlines, a communication gap between the developers and the business analysts and testers and of course unmaintainable codebase. In a team, we want all the participants to be able to speak the same language.

I conclude that there are two ways of constructing a software design: One way is to make it so simple that there are obviously no deficiencies and the other way is to make it so complicated that there are no obvious deficiencies. The first method is far more difficult¹.

Ultimately, what most of developers try to do most of the time is to read the source code and understand it. Only a small percent of the development process is dedicated to the actual implementation. However, eventually, developers have at least two tools to understand a system:

- Testing (our system is a black box and for specific inputs, we are waiting for specific outputs — examining from the outside)

- Informal reasoning (the case-by-case mental simulation of the behaviour of the system — examining from the inside)

However, when it comes to Testing and Informal reasoning, thus, the understanding, there are two factors which impact both of them drastically.

- State

- Control

The main problem which comes from the State in large scale systems is the difficulty to test and to reason about all the possible states of this system. In most of the cases, the number of possible scenarios that we have to consider and keep track of grows as long as the state grows. In fact, it’s very difficult to have a clear view of the state, particularly in large systems. If you have concerns about how important the state is for our systems, think about why your intuitive action when you have an unexpected error in your mobile phone or your computer is to restart it.

From the complexity comes the difficulty of enumerating, much less understanding, all the possible states of the program, and from that comes the unreliability¹

And of course, the other aspect is Control or in other words the order in which things happen, thus, the extra mental effort to understand a system. When the developer acts as a virtual compiler in order to specify how things work instead of what is desired from the system. You will read the word “behaviour” frequently in this article and this is on purpose in order to understand what is the key in this mental shift that we want to achieve.

So, do we have a way to keep track of and visualise all these different states that our system can have? Also, can we reduce the mental effort that is required to reason about the order in which things happen in our system?

How State Machines help us reduce complexity

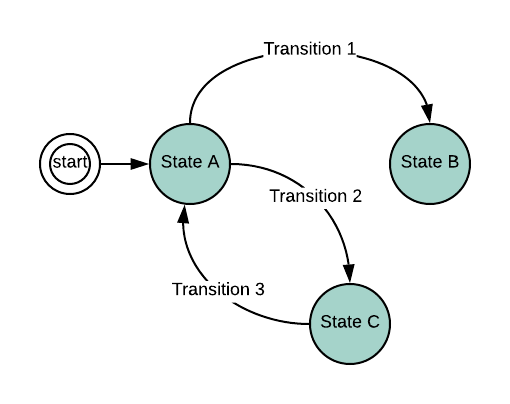

States and State transitions using a state diagram

States and State transitions using a state diagram

First things first, what is a State Machine? A finite-state machine (FSM) is a mathematical concept which was introduced in the early ’40s. It is an abstract way of thinking about how computers and computations work and they are especially useful for describing reactive systems such as user interfaces that need to respond to events from the outside³. The FSM can have different states, but at a given time fulfils only one of them. The FSM can change from one state to another in response to some external inputs; the change from one state to another is called transition. There are different types of FSMs. The one that is more suitable in the UI development is the Mealy machine where each transition to a new state depends on the current state and the current inputs (events, actions). Does this remind you of anything? A reducer for example?

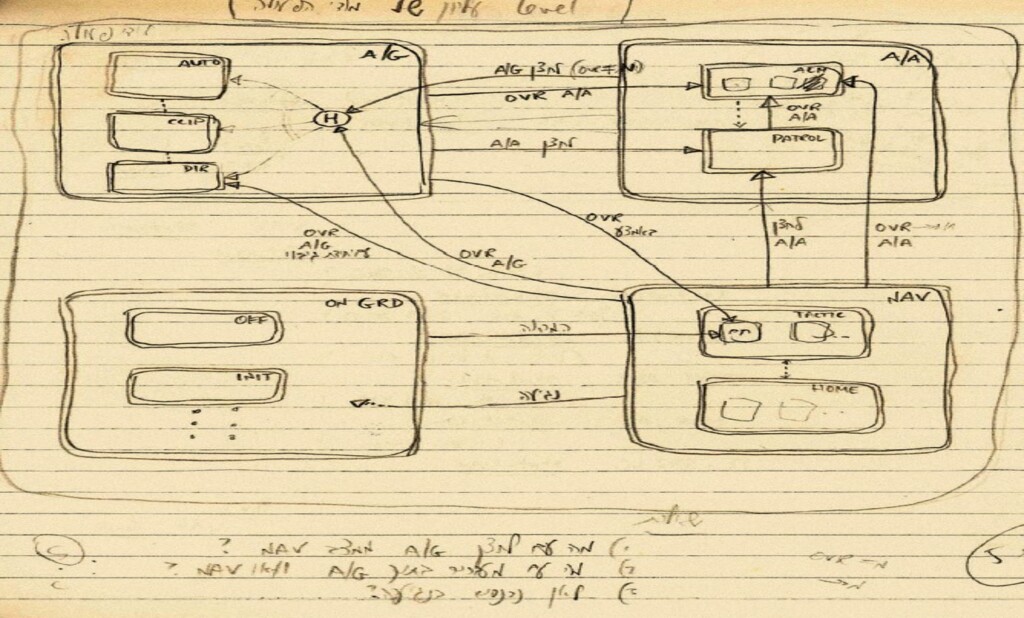

In 1983, David Harel² took state machines one step further by introducing the statecharts during his work in the Israel Aircraft Industries (IAI) trying to formalise and make the documentation for the systems in the IAI more accurate. His main goal was to collect all this distributed information from the documentation and to give a tool to the engineers of IAI to express what they had in mind and the intended behaviour of the system that they wanted to build.

A statechart is an extension of state machines; Generally, they can have:

- Nested states

- Parallel states

- History states

- Transitions can be guarded

- Transitions can be delayed

- etc

Statecharts are a formalism for modeling stateful, reactive systems. This is useful for declaratively describing the behaviour of your application, from the individual components to the overall application logic.

XState

XState is a library for creating, interpreting, and executing statecharts. Maybe the best part of this tool is that it forces us to focus on the problem itself first and then to attempt to implement a solution. Apart from this, when working with statecharts, we have to identify and visualise all the possible states. And this formalisation of the possible states is one of the tools that we can use to reduce the mental effort, hence the complexity of our problems.

In order to understand how we can work with XState in Angular, I will describe a real-world example. What we’re going to implement is a part of the gothinkster/realworld application. More specifically we are going to implement the login page of this application and we will cover some of the concepts of this library. Also, we’ll see how we can implement them in an Angular project (in the future we can extend our implementation to cover all the specifications and pages of the gothinkster/realworld project).

You can find the source code in the following Github repository.

Implementation

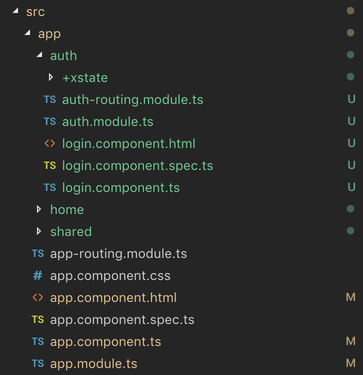

The first step was to create a new project using the angular-cli and to add some modules and components. The auth module contains the login component and also the +xstate folder. This folder contains the whole logic around our state machine for the login page. The plus sign it’s just a convention. Using this symbol, it’s very clear on every module where your statecharts’ logic is and also the folder is always the first folder in your module.

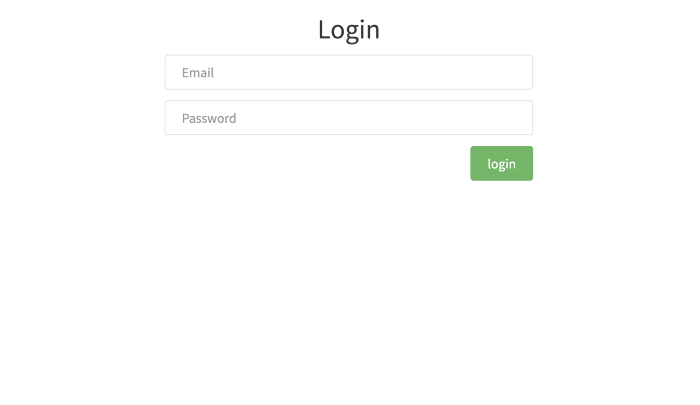

Login Page

Login page

Login page

In the login page, we just have a form. The state machine is very simple. The main reason for this is that in Angular Reactive Forms the state of the form is “hidden/embedded” in the form instance and it would be a disaster if we tried to replicate this state in our state machine. There is no reason to do something like that.

The first thing that we have to do is to think about the behaviour that our login page should have and try to model this behaviour with a statechart.

The behaviour of the login page should be as follows: When the users enter in the login page they should be either already logged in or logged out. If there is a validation error in one of the fields, then the login button should be disabled. When the user pushes the login button and there is a problem with the connection to the server, the user should be able to see the errors and to push the login button again.

States

The first step is to define the authMachine configuration object. We do it with the help of the Machine factory function. In this initial configuration, we try to identify all the possible states of our state machine. For the login page particularly, we have an initial state which is the boot state (from this state we transition immediately either to the loggedIn or to the loggedOut state based on a condition). The next state that we can have after the user enters the credentials is either a loggedIn state if the login is successful or the requestErr state if the request fails. During the request to the server, we have one more state which is the loading state. Below, you can see an initial configuration of the state machine based on the states we just defined.

//AuthMachine initial configuration

export const authMachine = Machine<any, AuthStateSchema>({

id: 'login',

initial: 'loggedOut',

states: {

boot: {},

loggedOut: {},

loggedIn: {},

requestErr: {},

loading: {}

}

});XState is written in Typescript and as you may understand it’s very useful to strongly type the state machines. In the above snippet, we have provided the AuthStateSchema generic parameter to the Machine() factory which enables us to determine which keys are allowed in our states configuration object.

export interface AuthStateSchema {

states: {

boot: {},

loggedOut: {};

loggedIn: {};

requestErr: {};

loading: {};

};

}Transitions

On every state node we can add the on property which defines which will be the next state based on the current state and an external event which triggers the transition from the current state to the next state. A state transition can be defined with a transition object or an array of transition objects.

//transition object

SUBMIT: {

target: ‘loading’

}//we can omit the target property

SUBMIT: 'loading'Events

To transition from the current state to the next state based on the transitions we have defined, we need to send an event. An event is an object with a type property which identifies the event and it can also have some other properties (payload).

//event

{

type: ‘SUBMIT’,

username: 'test',

password: '1234'

}It is possible for an event to be null, which means that the type is an empty string and it occurs immediately once a state is entered. We use null events to define transient transitions which are transitions immediately taken based on a condition.

//transient transition

on: {

'': \[

{target: 'loggedOut', cond: 'isLoggedOut'},

{target: 'loggedIn'}\]

}Such a transition is the initial state (boot) of the state machine. This transition is immediately taken when we load the login page and if the user is already loggedIn, then we transition to loggedIn state, else if the user is loggedOut (cond:'isLoggedOut' ), then we transition to the loggedOut state.

Guards (Conditional Transitions)

In order to implement this conditional logic, we are going to use a special kind of transitions which is called Conditional Transitions or else Guards. Guards are specified on the .cond property of a transition. Below you can see the implementation of the isLoggedOut guard.

@Injectable()

export class AuthMachine {

authMachineOptions: Partial<MachineOptions<AuthContext, AuthEvent>> = {

...

guards: {

isLoggedOut: () => !localStorage.getItem('jwtToken')

},

...Effects

If the current state is the loggedOut state, then we can only send a Submit event. After that, we transition to the loading state. When we enter the loading state, a side effect (requestLogin) is invoked which triggers the login API call.

...

states: {

...

loggedOut: {

on: {

SUBMIT: [

{

target: 'loading'

}

]

}

},

loading: {

invoke: {

id: 'login',

src: 'requestLogin'

},on: {

SUCCESS: {

target: 'loggedIn',

actions: ['assignUser', 'loginSuccess']

},

FAILURE: {

target: 'requestErr',

actions: ['assignErrors']

}

}

...

}And the implementation of the side effect:

...

@Injectable()

export class AuthMachine {

authMachineOptions: Partial<MachineOptions<AuthContext, AuthEvent>> = {

services: {

requestLogin: (_, event) =>

this.authService

.login({ email: event.username, password: event.password })

.pipe(

map(user => new LoginSuccess(user)),

catchError(result => of(new LoginFail(result.error.errors)))

)

}

...As we can see, based on the result of this event, we trigger some other events (LoginSuccess, LoginFail) which make our state machine transition to either the loggedIn or the requestErr state.

Actions

Unlike Side effects, Actions are fire-and-forget “side effects” which means that after their execution, they don’t send any events back to the statechart. We use them in our implementation to update the context of the statechart. The context is an extended state which represents quantitive data of our application. If the login is successful, we assign to the context the logged in user (assignUser). If the login fails we assign the errors (assignErrors). Also, we trigger one more action in order to update the local storage with the user’s token (loginSuccess). Below, you can see the implementation of these actions.

@Injectable()

export class AuthMachine {

authMachineOptions: Partial<MachineOptions<AuthContext, AuthEvent>> = {

...

actions: {

assignUser: assign<AuthContext, LoginSuccess>((_, event) => ({

user: event.userInfo

})),

assignErrors: assign<AuthContext, LoginFail>((_, event) => ({

errors: Object.keys(event.errors || {}).map(

key => `${key} ${event.errors[key]}`

)

})),

loginSuccess: (ctx, _) => {

localStorage.setItem('jwtToken', ctx.user.token);

this.router.navigateByUrl('');

}

}

};Visualise the state machine

We can also visualise the final configuration of the state machine and who knows, maybe we could discuss the result with the Business Analyst in our team in order to agree on the final business logic of the login page beforehand.

Visualise state machine

Visualise state machine

Vision

In my ideal world, the Business Analyst would be responsible for drawing up the state machine configuration as part of the task specification and this state machine would be committed on GitHub or BitBucket ready for revision and part of the actual implementation process. In this way, the team would talk the same language and we would be able to avoid most of the misunderstandings. I hope you found this article useful.

Special thanks to Aristeidis Bampakos and Giannis Smirnios for the extensive reviews♡.

Bibliography

[1]:Ben Moseley, Peter Marks (February 6, 2006) Out of the Tar Pit http://curtclifton.net/papers/MoseleyMarks06a.pdf

[2]:David Harel, Statecharts in the Making: A Personal Account http://www.wisdom.weizmann.ac.il/~harel/papers/Statecharts.History.pdf

[3]: CS 211 Spring 2006 State machines (Notes by Andrew Myers, 5/1/06) http://www.cs.cornell.edu/courses/cs211/2006sp/Lectures/L26-MoreGraphs/state_mach.html